Bloggers Unite For Refugees (Rwanda)

linocuts by Duhirwe Rushemeza

Today, Bloggers Unite focuses on the plight of refugees. The organization offers lots of links and groups to spread awareness about refugees but I decided to share my personal experience with Rwandan refugees. Two years ago, I was assigned a story on Rwandan refugees in Chicago. Although I specialize in African and Caribbean culture and travel, locating recent Rwanda refugees in the maze of shadowy and hesitant new immigrant culture truly tested my reporting skills. The first thing that I discovered is that despite media pronunciations, the country is called Wanda, with a silent R, by Rwandans. It wouldn't be my only lesson in the yawning gap between media portrayals of Africa and the reality. When I finally found Claude, a soft-spoken Rwandan, almost a month later, he wasn't even living in Chicago but a distant, rural enclave of the city.

Although I had seen and cried through Hotel Rwanda, hearing Claude's personal account is an experience I will never forget. Ever. I also interviewed Duhirwe Rushemeza, a talented Rwandan artist who memorializes Rwandan orphans with stunning linocuts, which are displayed throughout this post. I learned a lot that movies can't tell you. I witnessed the Rwandan spiritual strength first hand. I gazed into eyes that will always be haunted. I felt the hope that only unfaltering faith can bring. According to the BBC, 3.2 million Rwandan refugees returned home after the genocide. But thousands are still hesitant and fearful. There are 34,017 Rwandan refugees in the Democratic Republic of Congo and 20,952 in Uganda. Here's an excerpt from my story:

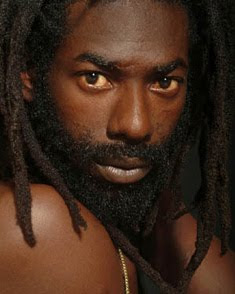

Claude Munyankindi speaks with a gentle, softly modulated voice. He stretches his long legs out and cradles his bare foot, much like a child who's been made to sit too long. But there's nothing child-like about Munyankindi. At 24, he's still a young man, eagerly anticipating his graduation from Trinity Christian College and the start of a medical career. As biology major, he studies long hours with rare moments of leisure. This is not what makes him seem older than his years. Nor is it the beard, mustache and receding hairline. It's his eyes, round and fawn-colored, that speak a thousand words about things no human should ever witness. He may be only 24 but Munyankindi’s eyes reflect decades of a nation’s sad and tormented history.

"I was 13-years-old in 1994," he says matter-of-factly. That particular year holds significance because as a Rwandan, he will always remember 1994 as the year that he was prematurely forced to become a man. It was the year of the Rwandan genocide. Munyankindi's father was killed, as well as his mother’s entire family. Their house and everything they owned except the clothes on their backs, was burned to the ground. Miraculously, he and his immediate household of eight people managed to escape the brutal killings. Nevertheless, Munyankindi and his family were the exceptions to a very bloody rule.

From the night of April 6, 1994 through mid July, 800,000 Rwandans were killed in the space of just 100 days. According to the British Broadcasting Company (BBC), it was the largest and most ruthless genocide Africa had witnessed during modern times. Located in central Africa, Rwanda is a small country, the size of Maryland. The nation is the most densely populated in the world and among the poorest. Rwanda’s three ethnic groups, the Tutsi, Hutu and Twa, boasted a history of cooperation and interconnection until the Belgian colonialists arrived in 1916. Declaring the Tutsi minority superior, the Belgians set them up for greater education, employment and leadership opportunities. They also ordered all Rwandans to carry identity cards, ensuring that ethnic differences would always be at the forefront of the people’s awareness.

Resentment against Tutsi privilege simmered for decades until a civil war in 1959 claimed an estimated 20,000 Tutsi lives. Many more fled to neighboring Burundi. Just before relinquishing power, the Belgians switched their allegiance and when Rwanda gained independence in 1962, it was under a Hutu government. Tutsi’s continued to be treated as scapegoats however, and they experienced massacres of several hundred people during the early 90s.

But nothing could prepare anyone for 1994. Tutsi refugees in Uganda had formed the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) and had established a dramatic military advance in 1993, demanding a peace settlement and shared power from Hutu President Juvenal Habyarimani. On his way back from signing the treaty in Tanzania on April 6, 1994, Habyarimani’s plane was shot down. Slaughter of Tutsi’s and moderate Hutus started that night and didn’t end until an estimated 800,000 were hacked with machetes, bludgeoned with clubs or shot.

"We knew it was coming because of all the years of civil war," recalls Munyakindi. "After the president got killed it all went down hill. The capitol (Kigali) was under siege and it took three weeks for the army to reach our region in Butare. The soldiers had a list of all the people targeted. Our family was on that list."

Somber faced and resigned to the facts, Munyakindi can’t conjure up words to describe the fear that he and his family were feeling. His eyes cloud over with melancholy as he flatly recites his experience. "They went from house to house, shooting people. My dad was an agricultural engineer and a high school teacher. He tried to negotiate and protect us. But they threw grenades on the top of our house. It blew away half of the house but nobody was hurt. My mom has headaches to this day because of that.”

After that, the family decided to try to escape. Munyankindi's father insisted on staying behind to negotiate the family’s safety, promising to meet up with them later. "We waited for our dad. He didn’t come. We went to the next city and waited in the refugee camp but we never heard from our dad. We later heard that he had been killed the same day we left.”

The family's ordeal was just beginning, however. For four months, they stayed in a refugee camp in the Congo with the threat of death constantly hovering around them. "We prayed a lot. There were so many days of close calls. We had documents but they knew we weren’t telling them something. We didn’t look like everybody else. We fit the stature of Tutsi people, tall and slim. We kept lying. My sister said our dad was an officer in the government army and he’d be back to get us. They would take people out and kill them everyday." Shaking his head with bewilderment, Munyakindi acknowledges that they were the lucky ones. "Our whole family, all eight of us, except my dad, got out by the grace of God. Most people lost everybody."

Indeed, there are currently more than 600,000 orphans in Rwanda, according to PBS. An estimated 200,000 of those were orphaned because of AIDS. During the genocide, men known to be infected with HIV raped women rather than killing them on the spot. This fact, coupled with the rampant killings meant that the odds for a Tutsi family’s survival were very slim. These odds are not lost on Chicago-based Rwandan artist Duhirwe Rufhemena. "70 percent of Tutsis were killed. My mom lost over 70 members of her immediate family. The odds were not in our favor, I don’t think I would have survived and it’s rare for an entire family to make it," she says. Born into a diplomat’s family in Kigali in 1977, Rufhemena ‘s family had been living in the Ivory Coast but was preparing to move back to Rwanda in 1991, when the civil war was starting. “It was a very dangerous time so we didn’t go. That’s what saved us."

Remembering the Rwanda of her childhood, Rufhemena says that she was never aware of any ethnic differences. “We were really happy. We were never exposed to the ideas of separation of the ethnic groups although they were always there.” It wasn’t until she was a teen that Rufhemena’s parents explained the ethnic tensions that plagued Rwanda.

"When the war broke out in 1991, they explained to us why it was happening. They didn’t subscribe to those beliefs but many people did. That’s the first time I understood the difference between Tutsi, Hutu and Twa."

In 1997, at 20-years-old, Rufhemena returned to Rwanda. "I saw all these orphans and victims of the genocide, homeless and some were invalids. The Rwanda that I remember as a child, you didn’t see children on the street. You didn’t see children trying to hustle. I was very affected by this. I went back to Spelman (college) and I thought, ‘I want to do something to help the children’ but I didn’t know what."

After taking a printmaking class, Rufhrmena created prints of some of the children she saw, selling them for donations to send back to the children. For her senior thesis, she designed an installation that documented how the genocide had affected Rwandan children and how the rest of the world related to the tragedy. "I really wanted to let people know what happened and be a voice for these children," she says.

Today, Rufhrmena’s art still focuses on Rwandan genocide orphans but her perception of them has transformed. “I went back in 2002 and met a boy who changed the whole way I look at their situation,” she says. "He was only eight. He made an instrument and played it to earn money. He was really independent, going from town to town. I started to look at them less and victims and more as survivors. A lot of children didn’t give you a chance to feel sorry for them because they were too busy living. They were resilient and the war had made them tougher"

Despite the horrific details of the genocide, the aftermath has indeed demonstrated the strength of the Rwandan people. Although the country has the highest proportions of orphans in sub-Saharan Africa, the government has passed a national policy establishing a framework to protect them. School fees have been eliminated and primary school enrollment has grown to 75 percent. With women comprising almost 60 percent of the population 12 years after the genocide, they also hold 49 percent of Chamber of Deputy seats within the Rwandan government. As a result, this small African country surpasses Sweden as the country with the highest percentage of women in a house of parliament. In the shadows of the genocide, a new Rwanda is developing.

To help refugees please contact Refugees United.

Comments

In Jamaica we say ee rac, I've always wondered what is the correct pronunciation. I enjoyed typing that the second time around :).

You're right, that arrogance irks me. I'm even more vexed 'cause my alternatives are limited.

I prefer the BBC, the tone of their programming tends to be respectful irrespective of who the story is about, and their coverage more extensive.